The short version: A dynamical system is a mathematical structure with a set of variables and a description of how they interact over time. Some of these systems converge onto what are called “attractor basins”, where many variables are simultaneously in an unusual and persistent state, but no particular variable can be singled out as the cause. This might be a fruitful way of thinking of psychiatric disorders.

The long version:

1. What is a dynamical system?

Some of the other pages on this site describe conditions as “dynamical systems”, complicated combinations of many variables interacting in nonlinear ways that produce chaotic effects. I think almost everyone is implicitly working off this hypothesis, but the only people I can find who discuss it openly are a Dutch team centered around Borsboom et al, and even they don’t think of it exactly the same way I do. This page is intended as a gentle introduction to these kinds of systems. It will start with a more mathematical explanation, then move on to a long and bizarre metaphor which I hope will give you some of the same intuitions I have even if you don’t entirely get the math. I’m not a mathematician, not an expert in dynamical systems, and I may be getting some or all of this wrong.

Imagine Alice has a chronic disease. Luckily, as long as she has a job, she will have health insurance. And health insurance provides her with a treatment. Every day she takes the treatment, her health will go up one point on a 0-100 scale; every day she misses the treatment, it will go down one point. If her health ever gets below 75, she will be too ill to work.

Mathematicians would call this a dynamical system with three variables: does she have a job or not, does she have insurance or not, and her health level. We know from the rules above that j always equals i, and that j is 1 as long has h is 75 or higher. And every day i = 1, h goes up one; every day i = 0, h goes down 1.

Alice starts with a job and health of 100. Since j = 1 and i = 1, health goes up one each day, but it’s maxed out at 100 so it just says there. This state is perfectly stable; as long as the system follows the rules above, it will never change.

Suppose Alice gets a mild cold which knocks her health down to 90. She keeps working, her health keeps going up 1 each day, and she eventually gets back to 100.

Suppose Alice gets a medium flu which knocks her health down to 80. She keeps working, her health keeps going up 1 each day, and she eventually gets back to 100.

But suppose Alice gets a serious pneumonia which knocks her health down to 70. Now she can’t work, she loses insurance, her health starts going down 1 each day, and she eventually goes down to 0. This is another stable state; as long as the system keeps evolving according to the rules, it will never change.

Let’s be more specific: the mathematicians would call this a dynamical system with three variables and two attractor states. An attractor state is a stable situation that tends to “suck” nearby unstable situations into it. Alice having a job, insurance, and health 70 is an unstable situation; she will immediately get fired, lose her insurance, and have her health start going down, until she reaches the stable (j = 0, i = 0, h = 0) attractor. Likewise, Alice having no job, no insurance, and health 90 is an unstable situation; she will get hired, get insurance, and have her health start going up until she reaches (j = 1, i = 1, h = 100). These are the only two stable attractors; any other situation will eventually turn into one of those two.

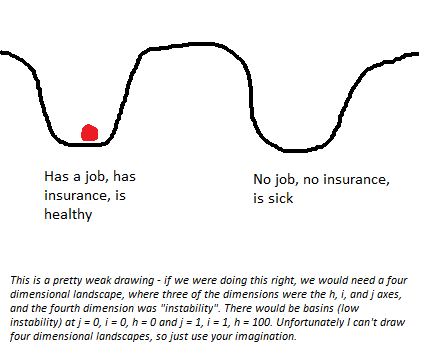

We can visualize this as a terrain with hills and basins:

If the ball is anywhere other than at the bottom of the basins, it will roll into the nearest basin, then stay there until acted upon by an outside force. There are two possible basins of stability – Alice having a job, insurance, and being healthy, and Alice having no job, no insurance, and being sick. If something else is true, she will drift to whichever of these two equilibria is closer.

This is an interesting twist to the recent discussion about taxometrics; it introduces change over time. Two of the variables in our system (job and health insurance) are categorical. One (health) is dimensional – it can be anywhere from zero to 100. The system itself is supposedly dimensional (there are lots of places it could be) – but in reality will mostly be categorical (it will tend to one of two very different attractor states). Even health, a supposedly dimensional variable, will tend towards either 0 or 100, making it look categorical.

Anyone measuring Alice’s health will occasionally find that it’s in places other than 0 or 100; these are not logically impossible. But a closer analysis will find that those two values are privileged and need further investigation.

2. How might dynamical systems be relevant to psychiatry?

Bob gets sad sometimes. When he’s sad, he stays in his room and refuses to talk to his friends. When he stays in his room and doesn’t talk to his friends, that makes him feel sadder.

You can already tell this is going nowhere good. You can imagine this system having two attractor states – Bob being happy and active, or Bob being sad and inactive. Each attractor state is stable until acted upon by an outside force. So happy active Bob will stay happy and active until (for example) he has a bad breakup with his girlfriend, after which he gets pushed into the (sad, inactive) state and stays there until something else changes.

According to the DSM, depression has eight core symptoms: low mood, lack of interest in activities, appetite change, slow movements, tiredness, feelings of worthlessness, poor concentration, and suicidality. You could imagine a dynamical system among all these variables, with each doing complicated things to the others, until they settled into some kind of attractor or other.

And by “you could imagine” I mean “Borsboom et al have mapped this”:

(source)

Every person has different connections between their depressive symptoms. Being sad might make Bob stay in his room, but it might make you go out and look for something to cheer you up. Still, we can notice some trends; people who are prone to depression seem to have much thicker connections than people who aren’t.

There’s another interesting Borsboom et al discovery. Let’s go back to our pictures of hills and balls.

Put the ball anywhere on the terrain, and it will slide back into the nearest attractor basin. But at different places, it will roll at different rates. On a steep slope, it will roll very quickly; on near-level ground, it will roll more slowly to start with. This is the phenomenon of critical slowing-down, observed in dynamical systems as diverse as

(also, some dynamical systems oscillate wildly between very low and very high points, which is pretty suggestive of bipolar disorder)

People often ask: is depression just the same thing as normal sadness? Taxometrics seems to suggest yes – it cannot find a categorical difference between major depressive disorder and normal low mood. But I’m not entirely satisfied with that answer, and dynamical systems theory offers a reason the answer might be no: depression is an attractor state in a dynamical system including normal sadness and many other variables. Normal sadness goes away after a few days or weeks; depression doesn’t.

So have Borsboom et al solved depression? I don’t think so. We know inflammation plays a major role in depression, so any dynamical systems perspective that doesn’t include a little circle for inflammation is going to be missing a lot of the picture. But the same is true of circadian rhythm, thyroid status, folate levels, and trauma history. Can you ever graph all of this effectively? Wouldn’t the graph start becoming so big and so complex that we stopped being able to conceive of it as a system at all?

3. How complicated can dynamical systems get?

Imagine some benevolent aliens surveilling Earth from orbit. They don’t understand our languages, and their own culture is so exotic that even very basic ideas like “money” or “war” are hard for them to understand. Still, they have good telescopes, and they’re able to measure some really basic things like how much light our cities emit, how much traffic is on our roads and sea-lanes, and how much smoke our industries emit.

After a while, they notice all these things are correlated. There are some years (for example late 1929 and the early 1930s) when city lighting, smoke emissions, and traffic all stagnate. In other years (like the late 1990s), all these things grow even faster than usual. After analyzing word frequency in human communications, they hypothesize that the former type of period corresponds to English “recession” and the latter period to “boom”. By performing sentiment analysis of human faces in the media during these periods, they hypothesize that we dislike recessions.

These are benevolent aliens, and they want us to be happy, so they wonder how to prevent recessions. Sometime during the 1970s, they notice that during a recession, there are fewer oil tankers leaving the Middle East, and longer lines at First World gas stations. They know enough chemistry to realize that oil is a pretty useful fuel at our stage of technological development, so they correctly deduce that the recession is caused by an oil shortage. This seems solveable! Using their Materialization Ray, they cause one billion barrels of crude oil to appear on the White House lawn.

This actually helps a lot! Light, traffic, and industrial emissions all return to normal. Sentiment analysis of human faces reveal a brief period of extreme confusion, followed by happiness. The aliens have successfully solved the recession.

In 2020, they notice another profound decrease in lighting, traffic, and factory smoke; looks like another recession. The aliens, still wanting to help and now confident they know how, materialize another billion barrels of crude oil on the White House lawn. The Earthlings continue sheltering in place from the coronavirus, but now they also have to deal with a billion random barrels of oil tumbling around Washington DC. The aliens have solved nothing.

These aliens are friends with the aliens simulating the universe, so they get a bunch of copies of Earth and run a bunch of experiments, until they feel like they really understand what’s going on. They present their results at the annual meeting of the Alien Planetwatchers Association (APA), and propose some general principles:

1. Recessions are fractally complicated. Not only do they have different causes, but the causes have different causes, and so on to infinity. For example, one recession might be caused by an oil shortage and another by coronavirus. But even oil shortage recessions are heterogenous. Some might be caused by production problems in oil-exporting countries. Others might be caused by political strife; the Arab countries place sanctions on the First World or vice versa. Still others might be caused by a shortage of supertankers to transport the oil. Still others might be caused by refinery failures that prevent crude oil from being turned into gasoline. Still others might be caused by trucking capacity shortages that prevent refineries from shipping gasoline to gas stations. Even that’s not enough layers; there are dozens of possible reasons for trucking capacity shortages, from bad weather, to labor disputes, to civic unrest, to a meteor hitting Detroit.

2. All of the possible causes of recessions interact with each other. If there’s a labor dispute at the trucking companies, that means gasoline sits undistributed at the refineries. But also, it means First World nations stop buying oil from producers, which could crash the producers’ economies, which could mean there isn’t enough crude even when the trucking starts up again. But also, the refinery workers might strike in sympathy with the truckers. But also, we don’t need as much oil, because truckers aren’t consuming it. But also, we can’t run the supertankers anymore because we don’t have enough oil to power them.

3. The way people react to a given problem is hard to distinguish from the problem itself, and the overall fractally-complicated mess of causes and effects depends equally on both of them. For example, the aliens might start out believing gas lines cause oil shortages, since they always see them at the same time. Later, they might do a time-series analysis and determine that gas lines are a consequence of oil shortages. But even this wouldn’t be quite accurate – gas lines are a consequence of governments rationing gas in order to alleviate oil shortages! If a laissez-faire government decides it’s not their responsibility to ration gas, you could have an oil shortage with no gas lines!

4. It’s very hard to determine the input or output of any given part of the system, because everything tends toward homeostasis in hidden ways. So for example, if a new and deadly coronavirus appears, it has the capacity to spread and kill millions. But maybe almost nobody will die, because governments institute lockdowns. If lockdowns prevent people from working, that should cause them to miss rent and get evicted. But maybe nobody gets evicted, because the government increases taxes on the rich and uses that to help people keep their houses. So death rates might stay almost the same, but wealth inequality would go down. An alien scientist studying this system from orbit and noticing a decrease in wealth inequality would have no way of concluding that a new and deadly disease was spreading. Everything has gone through too many steps to be legible.

5. If you zoom out, you can notice very broad patterns, but these patterns are protean and never share exactly the same features. For example, usually recessions have low inflation – but the 1970s recession had high inflation instead. Usually recessions see capital and labor suffer alike – but the 2020 recession saw very high unemployment with almost no damage to the stock market. So you can have a rule of thumb like “recessions cause unemployment, inflation, and lower stock prices”, but you should expect it to frequently be violated in ways you can’t predict. Presumably if you knew enough about the cause of a recession and the other things going on at the time (including what interventions humans were using to fight the recession) you could predict this kind of thing better. But even humans can’t do that, let alone aliens watching from above.

6. Interventions that work for one recession will fail completely for superficially similar recessions. Materializing 1 billion barrels of crude oil on the White House lawn will help an oil shortage recession but not a coronavirus recession. In fact, it won’t even help every oil shortage recession; an oil shortage recession caused by a strike at refineries will resist treatment with crude oil. Even if you choose the exact right treatment, it might fail because of other variables you didn’t consider. Materializing crude oil to treat a crude oil shortage will fail if the government is too corrupt to distribute it effectively. Or maybe the government tried to respond to the oil shortage by going green, and now everything is in the middle of a difficult transition to renewable energy, and so even though an oil shortage caused the recession the economy can no longer benefit from increased oil.

7. Most interventions have unpredictable side effects. For example, materializing thousands of hyperrefineries run by robots successfully solves recessions caused by shortage of refinery capacity. But it also puts tens of thousands of people out of work, and sometimes those people vote the socialist party into power, and sometimes that causes a recession even deeper than the original one they were trying to solve.

8. Almost any intervention can help or hurt a little, or sometimes both at once, often in completely unpredictable ways. For example, the time the aliens created one million lions in the center of Times Square was more of a test of the Materialization Ray than something they really expected to help, but this destroyed the city of New York, which hurt America’s bargaining position, which caused them to cave in to the demands of Arab countries, which convinced the Arab countries to resume sending oil a little sooner.

The APA Meeting mostly appreciates these findings, but some lively discussion ensues on a few more controversial points:

Professor Zaxyxon argues that their seemingly-successful treatments will have unexpected side effects. The more oil they materialize, the more likely Earth’s native oil industry collapses – nobody will be willing to pay for oil produced the usual way when magic oil keeps materializing from thin air. That means that as soon as the aliens stop materializing oil, Earth will go into withdrawal, finding itself with much less oil than ever before and suffering a catastrophic economic collapse. She suggests that either they avoid ever materializing oil at all, or they “taper” their oil shipments to give Earth’s economy a chance to recover.

Dr. Gorblax thinks that the aliens are wrong to focus so much on the “chemical imbalance” theory of recessions. Instead of attributing them to a shortage of oil, they should pay more attention to a history of trauma. As evidence, he presents his alternative theory that the 1970s recession was caused by traumatic memories of the various wars between Israel and the Arab countries, which led the Arabs to impose their oil embargo in the first place. Instead of materializing oil, they should try to help the Arabs and Israelis overcome their past trauma, which would lead humanity to resume producing oil naturally.

Dr. Xjvar insists that “recession” is a natural part of the boom-bust cycle, and that trying to treat it prevents human civilization from growing. For example, an oil shortage might encourage them to develop renewable energy, or a coronavirus epidemic might spur their investment in biotechnology. He thinks that pathologizing recession stigmatizes human civilizations that don’t focus on economic growth – but there are many other valuable things humans can focus on.

(if you’re seeing this in your mind’s eye, picture it all as being underneath a giant solid-light hologram advertising Vraylar. Nowhere in the galaxy is safe from the Vraylar ads)

4. What would it mean to think of the mind as a dynamical system?

The global economy behaves like a huge dynamical system. Everything affects everything else in so many different ways that it’s hard to keep track of.

If aliens tried to model the economy the same way Borsboom et al are modeling the mind, they would fail. They could pick ten important economic indicators – maybe employment rate, the S&P 500, inflation, and a few other things – and track how they co-evolved over time. This would probably be illuminating – for all I know some economist in our world is doing it already. But it wouldn’t be enough. They would never be able to predict a recession caused by conflict in the Middle East leading to an oil embargo leading to an energy shortage. Or a recession caused by deregulation of banks causing them to offer too many subprime loans and then getting called on all of them at once. They wouldn’t be able to predict whether government policy would shorten a recession or make it worse, whether international trade could help prop up a collapsing country or drag it further down.

At best they would sort of understand some of the principles behind why this sort of thing is so hard. They could understand that recessions (and booms!) are attractor states in a massively complex dynamical system, and come up with vague principles about how that system responds to certain shocks (eg “large stimulus packages can sometimes shift the system from recession to normal growth”).

I think the mind is at least this complicated. Just to take one especially well-understood example: some food includes vitamin B9. An enzyme in your body called MTHFR changes vitamin B9 into the active form l-methylfolate. L-methylfolate helps a waste chemical in the body called homocysteine turn into a helpful chemical called SAM-e, and prevents another helpful chemical called tetrahydrobiopterin from decomposing into a waste chemical called dihydrobiopterin. SAM-e and tetrahydrobiopterin are cofactors for the enzymes tryptophan hydroxylase and tyrosine hydroxylase, which change the amino acids tryptophan and tyrosine into serotonin and dopamine, respectively. And serotonin and dopamine are known to be heavily involved in mood and energy level.

Almost every step in this cycle is a potential depression treatment. Studies support l-tryptophan, SAM-e, and l-methylfolate supplementation as antidepressants (also, eating healthy in ways that get you more vitamin B9). But each step regulates all of the other steps in complex ways. For example, giving someone too much tyrosine might decrease the levels of tryptophan in their brain, because these two amino acids compete for a fixed number of transporters. The moral of the story isn’t “SAM-e good, homocysteine bad”, it’s “there’s a tendency for SAM-e to be good and homocysteine bad, but either one could help or hurt depending on how the system stabilizes after supplementation with either changes the state of all the other variables”.

(It might sound like I’m hawking companies like Methylation Genie that try to measure exactly how much of each of these you have in your body and tell you what your own personalized levels and deficiencies are. These companies would be great except for one thing: at present, we don’t know enough to do this effectively, and they don’t work. Yes, that includes whichever really fancy new high-tech company with lots of testimonials from hotshot doctors and professors is getting all the VC money this year. If we ever get anything that works better than trial and error, I will edit this paragraph to mention it.)

And this is just one tiny part of your metabolism. What we know about metabolism so far looks like this:

(source)

And that’s just what we know so far! Right now the best we can do is the same as the aliens’ best – drop a lot of chemicals down in random places, in a way that has worked pretty often in the past, and hope it helps more than it hurts.

In conclusion, taxometrics offers a useful way of understanding smoothed-out lifetime averages of mental disorders: as traits or taxa that differ among people. But many mental disorders evolve over time; depression comes in discrete episodes that start at some point and get better at some other point; bipolar comes in patterned waves of mania, depression, and euthymia. To understand these conditions, we have to add a dynamical systems perspective and think of episodes as attractor states.

Some mental disorders are pure traits without any dynamism – I think personality disorders, ADHD, and autism fall into this category.

Others are purely dynamical systems, where patients can sometimes be perfectly healthy, but occasionally they shift into a different attractor state. You could sort of think of this as having the “trait” of a weirdly-shaped attractor basin if you want, but there’s still a clear distinction between health and disease. I think depression and bipolar disorder fall into this category.

But most are combinations – patients have some consistent trait, but also sometimes have “flare-ups” where the trait gets worse than usual, or “good times” where the trait is better than usual. I think anxiety disorders, panic disorder, and schizophrenia are like this. There’s also a condition called “double depression”, which combines a constant dysthymia with occasional more serious major depressive episodes – an elegant demonstration of the independence of trait-like and dynamical disorders!